Vacant Building Registration Provides Data, Revenue, and Incentives for Building Re-Use

Last Reviewed: July 15, 2025

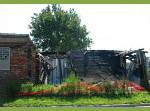

Vacant building registration is a tool growing in popularity in U.S. cities where unoccupied houses and businesses have become a big drain on neighborhood stability and the municipal treasury.

No one really knows how many of these ordinances are in place, but we have seen estimates as high as 1,000. We don't know of research yet on whether enforcement of these ordinances has been effective, but practitioners seem to think they are well worth pursuing.

Requiring property owners to register their empty properties with the city every year helps provide the city with better data from several standpoints.

Yes, cities can obtain data on likely vacancy from their own code enforcement officers as they drive through the city, they can purchase the post office's database that is usually pretty accurate, they can convince the utility company to alert them to very low usage of electricity, they may initiate a system for neighborhood associations to report vacancy, and they can obtain move-out data from other utilities. None of these systems are foolproof.

A much bigger data problem though is that in many states it is very common for rental properties to be purchased in the name of a Limited Liability Corporation, abbreviated as an LLC. The LLC usually is named something like the 100 Main Street LLC, and in many states the actual ownership stakes in the property cannot be discovered by the municipal government. Often the tax bills just go to an accountant or attorney, and neither of these can be held responsible legally for the condition of the building.

Therefore LLC corporations that are formed mainly for speculation or that are simply negligent feel they can safely ignore code enforcement efforts. In the best managed cities, they would be wrong in thinking this, but nonetheless, the LLC corporate form protects plenty of deadbeat building owners.

Vacant Building Registration Also Can Provide a Revenue Stream to Offset Direct Municipal Costs of Vacancy

The first few ordinances requiring vacant building registration imposed a minor fee to cover administrative costs of processing the paperwork. Now cities seem to be getting wiser to the actual direct costs of vacant property to the city. You might be thinking we are talking about costs such as conducting "sales on the courthouse steps," or the costs of boarding up buildings or mowing lawns.

Those can be significant costs in struggling cities, but the far bigger costs are those of fighting fires and dealing with crimes that involve vacant buildings as the setting or where the stash of stolen goods is stored.

So now we are seeing annual vacant building registration fees in the thousands of dollars rather than the low hundreds. The fee in Minneapolis is now more than $7,000 yearly, although the City waives that fee if it reaches a written restoration agreement with the property owner. Some cities are using a graduated scale in which the annual fees increase every year that the property is vacant.

We like the fee schedule imposed by Brooklyn Center, Minnesota. Not only does it scale up the longer the property is vacant, but also the fee may be reduced if there are no code violations. This leads to our final and most important reason to institute a vacant property registration process, which is obtaining code compliance and re-occupancy.

Using Registration As a Tool to Push for Re-Occupancy

Both the data and revenue considerations pale in comparison to the importance of preventing vacancy and addressing it rapidly when it does occur, in our opinion. Vacant buildings never get better on their own, so the goal should be a speedy re-use when vacancy does occur.

Sometimes landlords are less eager for a hasty resolution than you might think likely. Some property owners are merely speculating that the land and building will eventually be worth more than they paid for it, so they are not especially motivated toward the trials and tribulations of making a property rent-worthy and then selecting and dealing with tenants.

Others are discouraged property owners. Either they are discouraged with the condition of the property and overwhelmed by either the amount of expense or amount of work they would have to incur if they were to make it an attractive rental property, or they are discouraged that the market would not provide them the amount of rent necessary to finance all expenses of the building. So sometimes owners hide in denial for a while or for years. Often when the property owners are marginal economically, they talk themselves into thinking that eventually they will have more money and then be able to make a good profit on the real estate.

Many feel they cannot afford to invest the amount necessary to bring a good sale price, or that they could not possibly recover enough of their investment if they sold a piece of real estate in a declining neighborhood.

In still other cases, an estate owns the property. The heirs have determined that none of them want to live in or otherwise occupy the property. Perhaps there are disputes about who will pay which expenses as well. For more detail on this particular problem and some of the complications it causes, see our page on heir property that is shown in the row of photo links at the bottom of the page.

In a few other instances, the property owners are just kind of scoundrels and don't really care if they do the right thing. They certainly won't be swayed by the opinions of the neighbors. Code enforcement often doesn't work with these folks, at least until the measures taken become quite dramatic.

Regardless of the reason that the property owner is leaving the building vacant, the real goal of the municipality on behalf of both the public and the immediate neighbors should be achieving code compliance and re-occupancy. In the case of vacant commercial buildings, that re-occupancy might come with a change of use, as explained further on our adaptive reuse page.

So if the real goal is code compliance and prevention of further decline of the unoccupied building, ramping up the pressure on the owner through an annual vacant building registration fee helps provide the incentive for the owner to figure out their problem. If they are simply speculating, giving the owner a shove in the direction of selling it now without the expected windfall is great public policy.

If the issue is lack of resources, the municipality wishing to enforce its vacant building registration ordinance should be ready to offer information about programs for obtaining or financing necessary repairs. A variety of other types of information also might need to be provided for owners who appear paralyzed.

In addressing property owned by estates, for example, referrals to legal services or even family dispute mediation may be appropriate.

But for the scoundrels and speculators, the financial incentive of avoiding the annual registration fee plus hefty daily fines for violating the vacant building registration ordinance will be quite helpful in moving these property owners into code compliance or causing them to sell. Large fees will tend to pressure those accountants or attorneys who serve as owner's representatives for the anonymous real owners of an LLC to insist that the owners register.

We are in favor of making the fine for violation of the registration ordinance quite unreasonably large, and then publicizing that fact very vocally all over the city. This tool only works in the intended way, which is to inspire different behavior, if people believe that it will be enforced. Make the fine hundreds per day, if not thousands, if you can talk your city attorney into that. He or she may have legitimate concerns about how defensible that is, but make the fine as large as feasible.

Incidentally, Chicago tried to hold mortgage holders such as banks equally liable for registering the vacant properties they own, and for securing and maintaining them as well. This ended somewhat badly for the City of Chicago, as the Federal Housing Finance Agency prevailed in court. FHFA argued on behalf of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae mortgage holders that due to various technicalities, the federal government could not be forced to comply. Not all was lost, however; the Chicago did negotiate a settlement that achieved a bit of what it was seeking from banks who were somewhere in the midst of the foreclosure process.

Not so long ago, we felt we had to say that we were partly kidding when we proposed a vibrant downtown ordinance. Now that seems somewhat pale in comparison with the large fees and fines that some cities are imposing on owners of vacant property all over the city.

All in all, we like this tool because it creates quality data, opens up a new revenue stream to enable cities to address the very real costs of monitoring vacant property and responding to emergency calls associated with it, and gives property owners a substantial kick in the pants to get moving on doing something to remedy vacancy.

We just hope that cities don't get crazy with the fee they impose with the registration.

Read These Related Pages Next

- A Good Community ›

- Land Use Zoning and Codes › Vacant Building Registration

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.