Transportation Planning Determines Future Roads, Shapes Development Patterns

Last Updated: May 22, 2024

You are a beneficiary of transportation planning in some way, whether you're living in an urban neighborhood, suburb, smaller city, or rural area. Or perhaps you are more of a victim. Either way, on this page we will introduce what a planning commissioner, neighborhood leader, or interested citizen needs to know to understand the conversations and decisions that impact roads and other travel facilities.

Once one of our editors was involved in long-range transportation planning for a fast-growing county that apparently thought they were never going to grow when they had laid out two-lane roads as arterial streets.

The really interesting thing is that when she went back there 20 years later, transportation was the one and only aspect of planning that had been implemented pretty much as it was conceived earlier. This is the situation regarding major roads all over America, so the decisions made today really do matter.

It seems as though even in fully built environments, there is always some argument that relates to transportation planning. Someone will be advocating for widening a through street, installing traffic signals, or lowering or increasing the speed limit. At the local street level, people may think that others drive too fast, so we need speed bumps. We need stop signs. We should close off the end of this street. We should build a bike path along the old rail line. There are no sidewalks, and we need some. Or we do not want sidewalks taking up part of our lawns.

If you've been active in a neighborhood, town, or city, you've heard some of these transportation planning discussions. Below we start with major roads, because those too impact the local community and local planning commission decisions in a major way, and then we move on to a few comments about more local roads. Along the way we point out where to find information on other modes of transportation of interest to local people who are not planning or engineering professionals.

How Transportation Planning and Funding for Major Roads Occurs

Starting with the big picture first, every urbanized area in the U.S. has a federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) that performs transportation planning and makes allocation decisions about federal transportation funding. Virtually all major transportation projects are built using federal funds, even if those have been passed through to state transportation departments first.

They are required to base their transportation planning on the 3C’s--continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive. The boards of these MPOs typically consist of elected officials and political appointments, with state highway departments participating in transportation planning deliberations as well.

MPOs prepare and update two main documents:

- The Long-Range Transportation Plan, which is required to cover a planning period (often called a "planning horizon") of at least 20 years.

- The Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), which is a list of projects that is fiscally constrained. This means that a budget estimate of federal and local dollars available must be prepared, and that the projects cannot exceed projected resources.

It's important to note that the MPO deals not only with highway transportation, but also with allocation of funding for bus transit, bridges, bicycle and pedestrian facilities, streetcars, aviation, light and heavy rail, and marine transportation planning. The federal government supposedly rewards intermodal cooperation and may support intramodal centers financially. (A transportation "mode" means cars, airplanes, boats, vehicles, bicycles, and the like.)

So if you have any roadway in your area of concern that is a state or federal highway, our advice is that it's important to get acquainted with your MPO and its transportation planning functions. You'll find that state road re-builds are usually largely federally funded, so even states are highly dependent on the level and emphasis of federal funding. The link for finding your MPO is here.

You might find you are already quite familiar with your MPO, because some of them also function as regional planning and technical assistance agencies, run various programs, and serve as local councils of governments.

Periodically there are structured opportunities for public input, particularly at the time for the approval of the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP). Most of the MPOs aren't really very good at reaching out to the community, so you have to become assertive or even aggressive to be informed of the schedule for these. Typically there is a major update every four to five years.

You could encounter a wonderful MPO that is attuned to what residents want and to regional priorities and environmental sensitivities, or you could find that yours is going to do the minimum in terms of involving residents.

If yours is minimally effective, see if you can stir up some community organizations to make a larger impact. One positive development is that in the 2020's, a new emphasis on equity has been evident at the U.S. Department of Transportation; in practice, this means that the impacts of transportation systems on minority populations of many sorts needs to be considered in any transportation activities that involve federal dollars.

If your area of concern is confined only to locally owned and maintained roads or streets, you may be able to safely disregard the MPO and all of the federal transportation planning jargon, but there are a few exceptions to this generalization, so keep reading.

Level of Service Concept

We would like you to be aware of a key idea used in federal and state highway transportation planning, the "level of service." Commonly referred to as LOS in jurisdictions where the term is in use, this idea can be applied to almost any aspect of public service delivery where measurement is possible. That includes local streets.

Road LOS typically is expressed as a grade, as in elementary school, from A for excellence through F for failing. An F LOS represents a clogged road that takes way too long to travel, you're congested all the way, turns are difficult, and so forth. So LOS is an effective transportation planning tool. Some comprehensive plans include LOS goals for roads and other facilities.

Integration with Land Use Planning and Decisions

Before we move on to talk about local streets, we need to emphasize what is at stake. As described on the land use planning page, projected future land uses and future transportation needs are inextricably tied together. So land use planning without transportation planning is folly.

But the reverse is also true. Your public works department shouldn't be doing long-range transportation planning without considering the types of land use planning decisions that are being made. The staff for your planning and zoning commission should be completely tied into whatever transportation planning is occurring. The disciplines of planning and engineering have different cultures, but this is why the elected officials, planning commissioners, and interested citizens must insist that they find a way to work together.

All of this is easier said than done, due mostly to the fact that future land use plans usually are not followed as rigorously as transportation plans, and also to the fact that the MPO is planning for a much larger geographic area than most local governments.

Recently there has been a lot of conversation in professional circles about how autonomous vehicles, so called driverless cars (and trucks), will affect land use planning and the publicly owned space now devoted to road right-of-way. We've written about driverless cars and planning and aspire to keep that page current as the technology evolves and as states and cities begin to make decisions about how to handle the transition between our current situation and the coming revolution in transportation as driverless vehicles, probably electric and probably shared-use rather than privately owned, take hold.

We believe it is very important for citizen activists to begin to think about the transportation planning issues that will arise in that somewhat unknown future. We see that with the rise of the automobile, the decisions that were made did not anticipate the unintended consequences for cities. With this history in mind, we think you should be thinking about how widespread deployment of driverless vehicles will encourage sprawl, since people can multitask while commuting if they leave most of the driving to a computer. We can try to do better with the next generation of transportation.

Here we want to mention one relatively new initiative since 2021, which is called reconnecting communities. Recognizing the past inequity of dividing intact neighborhoods in two with interstate or other federal highways, frequently in minority communities, the U.S. Department of Transportation has started a pilot program to experiment with what happens when the major highway is converted back into a lesser roadway that would allow residents from both sides of the highway to interact again.

You might think it is heresy to demolish an interstate highway, but actually routing traffic into a dispersed grid of streets is likely nearly as efficient in terms of traffic flow. However, it is a lot more efficient in allowing movement of human beings from one side to another. Keep an eye out for the results of these experiments. (Yes, Portland already did this some time ago; it is not as if we are completely without data on the likely impact of this reconnecting communities effort.)

An interesting issue for some types of cities and states is the role of highways in bisecting wildlife habitat. Florida and some other states have tackled the issue of allowing endangered or just locally prized species safe ways to cross the highway.

Local Street Policies

If you have issues with your locally controlled streets, they likely fall into six areas:

- Maintenance

- Sidewalks and bicycle facilities

- Speeds (which may be a consequence of traffic volume and number of traffic lanes)

- Frequency and types of stops necessary

- Safety and convenience of turning movements

- Degree of connectivity, allowing convenient access to and from all destinations in town

Maintenance, in which we include potential street widening projects, depends on political will and money. Sometimes it's also a matter of smart assessment of where needs are most severe, and creative methods of addressing needs. For example, instead of the expensive and disruptive project of widening a street, potential solutions might be increasing the functioning and attractiveness of parallel streets and alternative routes, increasing the safety of pedestrian and bicycle travel on the clogged street or parallel streets, or even decreasing the speed limit if the primary issue is too many accidents.

On the repair issue, if your streets haven't been repaired in many years, it can be worth your while to hire a firm to evaluate what the least expensive and most durable fix might be.

I worked for a municipality that managed a very sophisticated program of repairing streets with different methods depending on identifying the underlying conditions, the solidity of the base, current and future traffic, and so forth. This generated major cost savings when compared with giving all streets the same treatment regardless of need.

So if you are maintenance-challenged, be smart, be selective, and possibly save money by avoiding the one-size-fits-all approach.

Regarding the second item in our list, bicycle and pedestrian issues, we have separate pages on each topic and refer you on to those pages.

To effectively discuss issues regarding speeds and stop signs or signals at City Hall, it is helpful to become familiar with the idea of traffic counts. Typically the counts are generated by pneumatic tubes over the road or by the newer methods of various electromagnetic or infrared sensors. The count may deliver just a basic number of vehicles over a 24-hour period, but most are programmed to report traffic on an hourly basis. A sensor in a turning lane can also provide information about turns. Be aware also that if you cannot get your city to run a traffic count, volunteers can count manually.

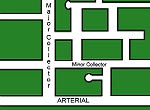

Also to discuss speed and stops, you quickly discover that transportation planning professionals divide city streets according to function and then base their judgments about what is appropriate on those categories. City streets are classified in almost all transportation documents, and the classifications are some variations of these three ideas, discussed and illustrated in more detail on our page about street hierarchy:

- Arterial streets. These function to move traffic through your city just as arteries function to move blood through your body. They are a key network, and ideally it's an interconnected network both internally within the city and to the edge of town where the arteries connect well into the state or federal highway system. Getting the arteries correctly placed and interconnected is key to good transportation planning. You may have major arterials and minor arterials, for instance, but you'll probably see some variant of this term if there's an official transportation plan, or transportation element (chapter) of the comprehensive plan, which might be called the master plan or general plan in your city.

- Collector streets. A collector street collects traffic from local streets. If you're a subdivision that has one or two access points to arterial streets or roads, the streets that intersect the arterials are the collectors. So a collector is intermediate between a strictly local street and an arterial street.

- Local streets. These may be a residential street that is not a "through" street, or commercial street that serves only a few businesses or industries and nothing else. Vehicles follow a local street to a collector street, and then to an arterial. Or so the theory goes.

Before the suburban building pattern became so prevalent, the street pattern of a city typically was a grid. In a grid, some streets may be designated as more prominent than others because they have fewer stops, a wider street with more lanes, or a higher speed limit. These variables are likely to determine how staff members will respond to your request to add more stop signs or reduce the speed limit, two very common requests received from neighborhoods.

To understand more about the classifications, visit our street hierarchy page. Also note the section about stops below.

Regarding safety and convenience of turns, typically planning commissioners must rely on police accident reports, anecdotes and personal experience, and any available traffic studies.

We need to take a small detour here to talk about traffic studies, which are prepared by a professional engineering firm. Along with current information and future projections about traffic volume, the study may include information about the number and percentage of vehicles turning each direction at intersections. Sophisticated analyses will include information about the wait times for turning at intersections that do not have signals. A good traffic study also segments different times of the day in its section on turns.

We have to caution that developers typically pay for traffic studies; occasionally the firm preparing the study slants the results to favor the developer, who is footing the bill. Just be aware of that possibility if you are a planning commissioner or city council member.

In the absence of a traffic study, planning commissioners need to be careful not to emphasize the anecdotes and personal experiences of particularly vocal members of the audience.

A planning commission member or citizen activist also should be concerned with the degree to which streets are connected to one another to allow an efficient street network. Occasionally there is too much connectivity, and it is appropriate to close off access from one area to another, but the plan commission and others should be wary of such requests since they sometimes indicate social snobbery more than good policy.

Sometimes in more distressed urban neighborhoods, people believe that closing off streets will reduce crime by discouraging criminals from driving down a dead end street. Boards and commissions should examine carefully whether that is actually the case in their particular city.

While it is very sound to require more than one means of ingess (going in) and egress (going out) as part of subdivision regulation, it is also important that subdivisions connect to one another. Benefits of such a policy include keeping some traffic off the major road and facilitating bicycle, pedestrian, and emergency and school transportation vehicle travel from one to another.

Lastly, we do not mean to leave out neighborhood traffic concerns, and in fact we have a separate page about them. This might include speeding, traffic controls and stop signs, cut-through traffic, and various traffic calming methods. Only rarely do these important but hyperlocal matters find their way into a regional transportation plan.

More About Signals, Signs, and Roundabouts

The time spent at intersections is the main variable determining the length of time a trip along urban streets requires.

It goes without saying that timing on traffic signals needs to be optimized to the greatest extent possible to allow traffic in both or all directions to get through quickly. Your city can program those boxes to the maximum extent possible to reflect varying conditions. Be aware that the potential for adjustment often is more limited on older signals than on the most recently installed ones.

If you are active at the neighborhood level, think two or three times before you ask for a traffic signal. Besides being expensive, they go out at exactly the wrong time, the timing becomes goofy because traffic conditions change upstream or downstream, and you're guaranteed to hit a long red light at 7 a.m. on a Sunday morning.

So consider whether the all-way or four-way stop won't serve your purpose. In most situations people proceed in quite an orderly fashion, and they're appropriate when traffic in the several directions is not too lopsided. If you have 90% of the traffic trying to process along one of the two roads, that's when you need a signal.

Traffic engineers work on the basis of what they call "traffic warrants." It means there is a written standard as to when a traffic signal or sign is "warranted." No, it doesn't have to do with warrants for anyone's arrest. Depending on the engineer, they may be rigid or somewhat flexible about applying those standards. But just like anything else at the neighborhood level, persist and insist.

Traffic circles have been common in some cities for years, but they are now very trendy in transportation planning. The theory is that it keeps more traffic moving faster because no one really has to stop; people entering the traffic circle, now commonly called a roundabout, yield the right-of-way gently to others as they merge. Then they leave the roundabout through perhaps a slight slow-down if necessary.

Proponents points out that since no one stops, there's no idling, which is good for energy savings and decreased air pollution. Also in theory, if it's a single-lane roundabout where there's no lane switching necessary to enter and exit, it's reasonably safe for vehicles, pedestrians, and bicyclists.

The reality is that these are good for aggressive drivers and not good for anyone else. If you have a muscle car and excess testosterone, this is for you.

But if you have an ounce of sympathy for Grandma at all, don't even think about it.

If you want anyone to look at your storefront, forget about it. They won't look; they're too busy noticing who's coming and who's going and what is on the other side of the circle. If you want to promote walking, forget it.

It's a really, really bad idea for most American places. Appropriate locations for roundabouts are extremely urban environments where more than four streets come together, where all streets are somewhat similar in traffic volume, and where pedestrian facilities are robust. This is why the roundabout works well in many European cities.

Two Hot Topics: Traffic Calming and Complete Streets

Traffic calming is any artificial device or procedure introduced to try to make traffic go slower, but not stop. So from the speed bump in the trailer park to the sophisticated chicane, in which a jog in the street is created, that's traffic calming.

The term also may extend to installing permanent or temporary barriers on a portion of the street, forcing everyone to enter a more narrow lane or to dodge from one side of the original roadway to another.

If you decide to try traffic calming, which is discussed more extensively on another page, be prepared for tantrums from within your neighborhood. So have a good neighborhood dialogue about the possibilities before any firm decisions are made.

There are a number of ways to test traffic calming devices temporarily, by the way, so it could be that putting out barricades for a few weeks where permanent obstructions are being considered would be a good test run.

A more inclusive concept is complete streets. In contrast to many single-issue traffic calming programs, complete streets emphasizes all users and all transportation modes.

A complete streets program is a long-range program in built-out areas, because implementation usually occurs as streets are rebuilt.

From a complete streets perspective, it's just as important to have a bikeable and walkable community as a drivable community.

Further, having a few blocks of bike lane that then disappear into multi-hazard territory for bicyclists just doesn't count under complete streets. Sidewalks that dead end into retaining walls don't meet the mark.

For either traffic calming or complete streets, making the treatment as aesthetic as you can will increase acceptance. Transit stops, bulb-outs, islands, short medians, chicanes, and street narrowing all offer substantial opportunities for landscaping, a small sculpture, or maybe a fountain.

Roads May Seem Rural Now, But What About Later?

And if you're in a small rural county government where no one is really planning land use, and where there's no zoning, you still need to consider future land use in your transportation planning.

In other words, do you think that each town will expand some in the future? Or will some of you rural by-ways become city streets if the city near you keeps growing? If you think so, it's more than likely that the expansion will follow the main road out of town. If you have a major attraction, such as a lake or a large employer, that could serve as a magnet for future building as well. Use your best intelligence as to what will likely happen, given the most optimistic scenario for growth.

Then, even though it seems inconceivable to you that you could need to widen that narrow little road, it you want building to happen there, do some transportation planning for the roadway.

I'm not saying you have to build a big wide boulevard now, and in fact it would be fiscally and environmentally irresponsible to do so. But leave the room for it.

As mentioned at the top of this article, when we return to what was once a 20-foot-wide rural road, in 20 years it may have turned into a five-lane wide boulevard. There's Olive Garden and Best Buy and You-Name-It, but all of this is possible because of transportation planning. If that road is designated as a future arterial street in the Long-Range Transportation Plan, in due time, the transportation plan will be implemented.

Now, rural folk with no planning or zoning, what if an 80 foot right-of-way that seemed ridiculous to ordinary folks (and the people who lived along the road) had not been set aside? The first chain store coming in would have built right at the intersection with an existing major road, and chances are excellent they would have built their side entrance too close to Little Rural Road that is now a true boulevard.

This is where you need an Official Map to make sure your transportation planning is preserved, even if you don't have zoning. Most states allow local governments to create an official map to set aside land for future roads.

The official map doesn't carry any funding promises, and it surely doesn't have to do with zoning, but it does say that land owners can't build in an area proposed on the official map for future right-of-way. Check into your state law about this subject; I think all of them now are published on-line so you no longer need to go to your county courthouse or go see an attorney to look up a state law.

So set up an official map if your state law permits, even if you have no land use planning or zoning function in the county. It lets you keep your future road rights-of-way clear of buildings that would expensive (and pesky politically) to buy out later if you need that road widened.

You can see we were only able to scratch the surface in this article, but we keep adding information to the website, or ask your community development question here.

Read More about Topics Relevant to transportation

- Making and Keeping a Good Community Development ›

- City Planning › Transportation Planning

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.