Transfer of Development Rights Can Preserve Farmland and Natural Areas

Last Updated: October 1, 2022

Transfer of development rights (TDR) programs help direct growth and density toward areas that can support additional intensity, while at the same time compensating farmers and other property owners in more rural areas for leaving their land "undeveloped" in perpetuity.

Right away we should tell you that our experience is that these programs are complex, subject to unintended consequences if not planned carefully, and sometimes underutilized. They are certainly no panacea for sprawl prevention, but in some circumstances, they are a promising option when paired with other sound land use policy on the part of the local government or governments involved. On this page we will point out some pitfalls we have seen.

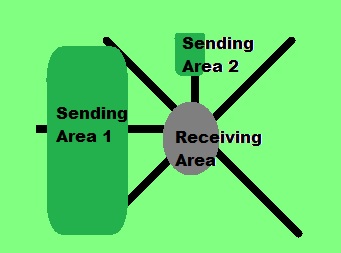

In brief, one or more local governments map "sending sites" and "receiving areas" for development rights through zoning ordinance amendments.

It is commonly said that real estate owners have a bundle of rights, so in a TDR program, owners of real estate that might reasonably be considered to be in the path of future suburban or urban development agree to peel off and sell one of their "rights," the right to reap the rewards of appreciating property value due to potential for future development.

Owners in the sending areas still retain ownership and the right to continue the current uses of the land.

The transfer of development rights occurs when an owner in the sending area sells the right to denser development to an owner in the receiving area, usually a developer. The developer in the receiving area then is granted the right to build more square footage, height, or other measures of intensity than is allowed ordinarily under the zoning ordinance.

The seller in the sending area typically places a conservation easement on his or her land, requiring that it be left "undeveloped" in its current state forever. Individual transfer of development rights programs vary, so the mechanism for enforcing the deal on sellers of their rights could be different.

As planners, we who publish this website have seen both landowners and developers become so disgusted with the complexity of the TDR setup that they simply walk away from the table. In at least one instance, we saw a developer move on to the next city. The take-away lesson is that any transfer of development rights program should be accompanied by a detailed web page and brochure.

An example will help if you're still confused. Imagine that the value of farmland in your area is $5,000 per acre and that farms being sold for subdivision development commonly fetch $25,000 per acre. The farmer sells development rights to a developer for $20,000 per acre and then executes a conservation easement to bind current and future owners to the agreement not to pursue urban development. Meanwhile the developer who paid $20,000 per acre is happy because he or she is about to make a much more lucrative and comfortable profit on a real estate development in the receiving area where infrastructure, the market, and surrounding properties already support denser uses. Maybe the developer could build only two housing units per acre under existing zoning, but now he or she can build at townhome density up to eight units per acre.

To help you understand the concept we've been talking as if farmland preservation is the only goal of transfer of development rights programs. The transfer of development rights concept is equally applicable to limiting development in hazard areas, such as areas adjacent to a fault or on a beach vulnerable to rising sea level, and also to preservation of historic sites.

How a Transfer of Development Rights Program Might Work

It's best to view the transfer of development rights program as a sophisticated technique to be used by local governments as a strategy for implementing a comprehensive plan that directs urban or suburban growth to certain areas and away from others. The government must take the lead in setting up the program because of the close relationship to the zoning ordinance.

Sometimes a city and a county, or more than one city and a county, or multiple cities, cooperate on the TDR project. This approach might yield excellent results as a sprawl solution, but it requires close cooperation to make sure both entities are integrating transfer of development rights into their comprehensive plan and zoning ordinance. This only multiplies the complexity of setting up and administering the program correctly, but such an approach can be a powerful tool in directing growth to where both market preferences of buyers and infrastructure will support that growth.

While the city or county draws the boundaries and enacts them typically as an overlay on the zoning map, the transaction between seller and buyer of rights is usually a free market transaction with the government not entering into discussions about price.

The government may set up what is often called a TDR bank to allow land owners in the sending area to "make deposits" of land without the prospect of an immediate buyer from the receiving area. The government typically then is paying the seller and waiting for the buyer to appear in order to be reimbursed. The local governments must provide clear information about how the TDR bank is operating, and make public the results, but the government is not a party to the actual sales transaction.

Here we should note in passing that some governments have initiated purchase of development rights (PDR) programs in which the government itself does buy the urban or suburban development rights. Usually this transaction also is enforced through a conservation easement, although occasionally deed restrictions are used. We recommend the conservation easements, with the local government itself or a conservation non-profit as the holder of the easement. But PDR is a different program than TDR and obviously requires deeper pockets on the part of the government. Purchase of development rights meets the worthy goal of stopping the sprawl of suburban development but does nothing to accomplish the positive objective of increasing density in parts of the city or region that could benefit from that greater intensity of land use.

Points to Consider for Setting Up TDR Sending Areas

1. Draw the boundaries of the sending areas generously enough that there will be a good supply of development rights available for purchase at any given time. Some property owners will not want to participate, preferring to wait to see if the TDR plan collapses or just to understand whether it really works. They also may think they can exert enough political pressure on decision makers to allow them to opt out of the whole process. Others just choose to remain oblivious to complex schemes they don't understand.

This calls for an early and complete orientation for property owners about any proposed system. If they are going to oppose it, you deserve to know that to give yourselves time to educate and persuade them.

2. An early decision you will face is determining the definition of one development right (sometimes called a credit). Often this is stated simply as a number of acres, as in one development right or credit equals one acre or more likely five acres.

3. Obviously you cannot allow sale of a development right if the land already is subject to a conservation easement or comparable deed restriction, so if you are in an area where conservation organizations already have been active in signing up property owners to donate or sell easements, the concept may not be viable.

4. Typically the minimum acreage required under the zoning ordinance to support an existing farmhouse and agricultural use are not counted toward the development rights that may be sold. The reason is that the owner will retain the right to continue the present land use and must be legally able to do so under zoning requirements.

5. Land that could not conceivably be used for development may be disallowed for the transfer of development rights. Examples would be ponds and possibly ravines and wetlands if the latter are restricted otherwise by federal, state, or local law.

6. Some experts advise downzoning the sending area before enacting the transfer of development rights program in order to make sure the increment between undeveloped and future developed value is large enough. We imagine this will lead to howls of discontent in your location, though, so you will want to think twice about doing this. Yet keep in mind that not every property owner in the sending area will oppose this program. Indeed many families like the general idea of keeping their land rural in character, but just find it hard to resist the big bucks that neighbors report if they sell their property for development. So if the rural households are reasonably happy about the prospective designation as a sending area, you can work with them on the downzoning idea.

Some Notes About the TDR Receiving Area Designation

1. In some cities it is difficult to identify appropriate receiving areas. Obviously there must be a market for the denser development in the area, or the entire TDR scheme won't work because no one will want to buy the rights. Just to expand on that thought to make sure you don't miss it, if buyers aren't enthusiastic about townhomes at six units per acre, and your zoning ordinance already allows up to five units per acre, you are wasting your time looking at this particular receiving area, or maybe at the transfer of development rights concept in general.

2. Extreme care should be exercised to ensure your intended result of positive additions to compact development within an already developed area. Some cities have ended up with developers using their purchased development rights to construct strip malls or large lot subdivisions that characterize the very kind of sprawl that the program is intended to prevent.

We can't give you blanket recommendations about how to prevent such outcomes, but we only advise you to take some real time with imagining worst case scenarios about how the purchased development rights might be misappropriated in your receiving area under your particular zoning ordinance. Yes, you can and should build in design controls or even a slightly different zoning district for properties where TDR is being applied, but that adds another layer of complexity to an already daunting set of steps. Then you have to consider that the market must be strong enough to thrive even under the new design guidelines, requirements, or review you are imposing. We suggest detailed interviews with developers active in your area to help you avoid a misstep.

3. The receiving area needs to be an appropriate size to allow some choice of properties for interested developers, but also not so large that developers and the public perceive little or no impact in return for all of the planning and administrative hassle of setting up and promoting the program.

4. The local government needs to exercise extraordinary discipline not to upzone properties in the receiving area except through the TDR program. The local government's firm pledge in this regard is important to making the transfer of development rights initiative work. If developers can go around the slightly cumbersome TDR program to get what they want anyway, why wouldn't they? They feel comfortable with rezoning and will opt for the known rather than the unknown unless the TDR benefits cannot be obtained through rezoning.

5. Figuring out equivalencies for the development rights is no minor task. The implied value must be high enough that land owners in the sending area will participate, but low enough that developers in the receiving area actually will want to become purchasers. Our experience is that the government should almost always hire a consultant with experience in transfer of development rights.

6. From the public standpoint, it is critical that the receiving area already have enough adequately sized infrastructure that can support development more intense than what is currently allowed under the zoning ordinance. If the government has to build new infrastructure just to make the TDR bank a success, in most cases, the project will collapse.

Administering TDR Programs

Administration typically includes a fairly lengthy application requiring the owner in a sending area to reveal ownership, structures on the site, a site plan, site conditions such as lakes or ponds that could not be developed anyway, mortgages, easements, deed restrictions, and anything else that already limits property rights. The government will want to verify these statements through a title report and a site visit. In contrast, often the application from the purchaser in the transfer of development rights transaction is rolled into applications for the specific development being proposed.

Sometimes a government will require a seller of development rights to prepare an acceptable management plan for the agricultural or forested land to ensure that the environmental and open space benefits of keeping the land out of development are maximized.

A major headache for the sponsoring government is making sure that the program is as immune from lawsuits as possible. Not everyone will love this program, and unhappy property owners in the sending area may say that their property has been subject to a "taking" and that they should be compensated immediately by the government. So making sure that sending area owners are treated well is of prime importance. Indeed, this is an argument for setting up the TDR bank so that fair compensation to sending area participants is immediate.

On the other hand, neighbors of the receiving area are quite possibly going to be very unhappy as well, since in effect the receiving area designation amounts to an upzoning. The knee jerk reaction against density may kick in.

Further legal preparation involves making sure that the TDR plan conforms very closely and explicitly to the comprehensive plan and its goals, and that the transfer of development rights program works seamlessly with the zoning ordinance, subdivision regulation, and any other land development and conservation ordinances that are in place. Federal and state laws become a big consideration for you if you are in a beach community or one with extensive wetlands.

Some states' planning and zoning enabling legislation explicitly mention transfer of development rights as a legitimate planning program. If your state law is silent on this issue, that is another concern about legal viability that your attorneys may want to address by adding as much planning and zoning rationale as possible to the ordinance enacting the TDR plan. Or the attorney may advise trying to amend state law.

Some cities have dealt with legal jeopardy by providing a hardship exemption process or allowing the government to make an outright purchase of development rights in cases of hardship.

To make these programs work even better, we think local governments may want to consider preferential treatment for highly desirable public outcomes, such as infill projects on a specific parcel downtown.

The best advice for planning commissions and activists who are investigating a TDR progam is to insist that the governments involved seek specialized professional help unless staff members and city attorneys have specific experience in this area. Given the right circumstances, the tool can be worth all of the hard work involved.

These Pages On This Site, Among Others, May be Highly Related

- Making and Keeping a Good Community >

- Community Challenges, Common Topics & Concepts >

- Urban Sprawl > Transfer of Development Rights

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.