Street Hierarchy Is Meant to Organize

Subdivisions, But It's No Way to Develop

Last Updated: June 19, 2024

The idea of a street hierarchy gained acceptance in the 1960s in the U.S. as a way to bring order to suburban streets, especially when a suburb was being built on green fields that had not been developed as urban land before. Soon thereafter transportation planning agencies began classifying all of the streets in a metropolitan area in this way. The idea persists today in the popular imagination, and to some extent among traffic engineers, city planners, and the urban design community.

The popularity of this idea is probably still on the rise in Western Europe, which has become increasingly interested in U.S.-style suburban development.

Here we should hasten to say that we are not necessarily fans of the street hierarchy idea at all; in fact, we think that if you are development a street system where none has existed, or if you have the opportunity to plan a significant redevelopment, you should avoid the street hierarchy notion.

A traditional system built on the hierarchy principle may feature unnecessarily wide collector and especially arterial streets. Maybe you should opt for a grid system that distributes traffic over a much larger number of streets. Hierarchical systems tend to concentrate traffic in a few locations, and then residents and transportation planners wonder why the community suffers from congested intersections and rush hour traffic jams.

So we offer this page as an explanatory tool for those who encounter this concept; do not interpret its existence as an endorsement of the idea.

How the Street Hierarchy Works

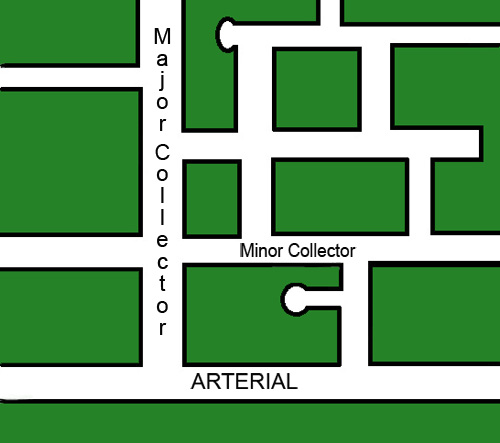

The conventional model of a street hierarchy works this way.

1. Many local streets (sometimes divided into minor local streets and local streets) distribute residents to their homes. Cul-de-sacs were thought to be highly desirable and by definition did not connect to any other streets. The cul-de-sac was felt to be the ultimate in family-oriented and child-oriented pedestrian safety. However, the pedestrian safety factor vanishes as we progress upward on the street hierarchy, as we will see.

2. The local street network, whether consisting of only one local street or a series of them, ultimately connects to a collector street. The collector is designed for a greater capacity moving at a slightly greater speed than the local street, and true to its name, it collects traffic from a number of local streets.

3. One or more collectors finally feed traffic onto the arterial, often a pre-existing street that simply was extended further into the hinterland to accommodate the latest subdivision or series of them. By this point a signalized intersection is in order if the collector carries much traffic at all. The arterial street is designed to travel at higher speeds, 40 miles per hour or greater. Of course, the ultimate irony is that the arterials only function as designed for a short time because often more and more development is permitted to enter the arterial, perhaps without a corresponding increase in capacity.

4. Traffic engineers of the day believed that the traffic signal would lead to maximum efficiency in the system. In many ways the typical street hierarchy is designed to route residents from single-family homes in a clearly understandable way, and at a predetermined pace, to the subdivision entrance where the driver encounters a traffic signal at the arterial.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Street Hierarchy Versus Street Grid Idea

Many large subdivision developments were designed with entrances from two arterial streets, giving two signalized places for the new residents to merge into the existing traffic pattern of a city.

Often both local streets and collectors were designed in a curvilinear pattern considered attractive at the time. Eventually the street hierarchy was actually encapsulated into many municipal codes, either through the subdivision regulation or the zoning ordinance.

This leads to two minor advantages of the conventional street hierarchy, described below.

1. It is commonplace still to encounter a town that names its major and minor arterials, and its major and minor collectors, in a comprehensive plan or a development regulation. The listing then becomes a de facto basis for other regulations such as speed limits, or required minimum driveway separation (or limits on direct access such as driveways in the case of arterials). To the extent that this is merely a convenient way of grouping existing streets, we suppose that there is little harm in the practice.

2. The street hierarchy theory of urban design was intended to organize residential communities, thereby making the system easy for drivers to decipher. Taken in isolation, this certainly is a worthwhile goal.

Notwithstanding these two small advantages of a street hierarchy, our website promotes the return to the traditional street grid when the opportunity arises. A major reason we make this judgment is because of the functionality and also the environmental benefits of having two or more alternative routes available when traffic volume, accidents, or construction make one route slow and difficult.

Another huge factor is that pedestrians and cyclists can take many of the short trips—and many of a town's trips are short trips of less than a mile—off of the street system altogether. If you think about it though, it’s not nearly as practical to take your bicycle or walk if you have to exit your subdivision onto an arterial and then move down the arterial to the entrance to the next subdivision in order to visit the neighbor whose back yard abuts your back yard.

The benefits to be gained by encouraging active transportation—the transportation that your body has to participate in—obviously include both physical and mental health.

The two transportation modes of cycling and walking do have the potential to be game changers in many subdivision environments where rush hour bottlenecks occur.

The street hierarchy traditionally did not look at interconnectivity between adjacent subdivisions and in fact sometimes actively discouraged any internal connections.

The specter of an awful thing called cut-through traffic was raised at many planning commission hearings. Subdivision residents didn't want their children kidnapped or their televisions stolen by people they didn't know from an adjoining subdivision. The unintended consequence was that the suburbanite's children had to be driven to the adjacent subdivision for play dates rather than sent or accompanied on foot to a very nearby lot.

The grid does require somewhat more right-of-way overall, and thus incurs a higher initial construction cost. Of course that greater embedded energy from the initial construction must be taken into account throughout the life cycle of the street when comparing hierarchical theory to the street grid. The lower cost of construction is one of the ways that the street hierarchy system was readily sold to subdivision developers.

Whether the demise of the street grid was the cause or result of a low-density residential preference is difficult to say and doesn't matter. What is important is that the huge advantages of redundancy inherent in the street grid can be regained if only the unquestioned dominance of the street hierarchy can be broken.

We are certain that the topography and the land use planning principles that a town or city wishes to follow are more important than the unqualified belief in either the grid or the hierarchy. We continue to love the grid, for the reasons outlined above, but it will be a long time before suburban retrofit can be carried out in every community.

It's not our purpose to demonize the street hierarchy, therefore, but simply to point out that we shouldn't build any new developments in that fashion.

If you are an elected official or a planning commissioner in a suburb, take a look at the influence of street hierarchy thinking on the functioning of your streets and even its impact on your density. Decide on a way forward, punching through connections between cul-de-sacs when an opportunity presents itself.

Then you can help to assure that your city actually follows through on your conceptual ideas by working to put the correction of these dead ends into the capital improvements plan.

Other Ways People Are Using the Term

By the way, there is a lot of silly terminology differentiation going on right now. Proponents of a road hierarchy theory of highways throughout a state or metropolitan region may tell you a road hierarchy is entirely different from a street hierarchy. In practice, well-meaning people blur the distinction all the time.

However, we should point out that many state highway departments use a street classification system quite effectively to group construction standards and performance standards in a reasonable way.

There are also some arguments out there about how a complete street policy or the roundabout replaces the idea of a hierarchy. Complete streets do not seem to us to be relevant to whether or not there is a hierarchy; we think any street with sufficient right-of-way could be made to be a complete street. Roundabouts do have a certain leveling function, allowing major and minor streets to intersect without stopping, but again we find that to be somewhat irrelevant to the grid versus hierarchy question.

These Topics Could Be Relevant to Classifying Streets

- Making and Keeping a Good Community >

- City Planning > Street Hierarchy

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.