Do You Live in a Smart City?

Last Reviewed: June 20, 2024

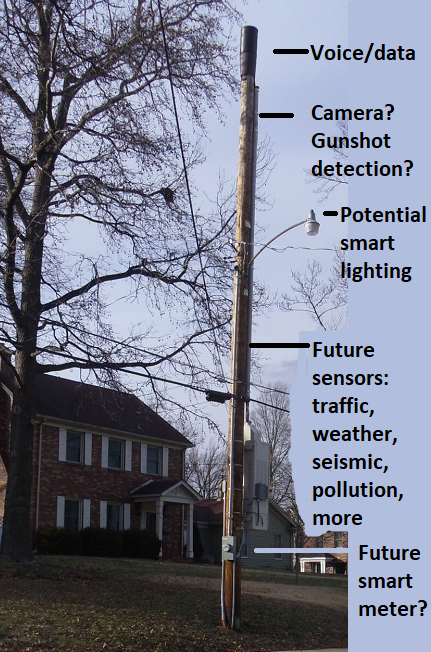

We confess that we wrote this headline for our smart city page partly with tongue in cheek, but we think poking fun at that term is richly deserved. Yet the term has gained enough traction it seems that we will be stuck with it for a while. Check out this photo and its labels.

What Is a Smart City?

Fundamentally people are using the term smart city for any and every function of a city government, its management, or public services that can be improved through use of digital technology. That is why you will need to question what exactly is being contemplated when you hear someone use this phrase. It is so broad as to be close to meaningless.

We would like to stick to a slightly stricter definition also in wide use. Specifically, the idea is that digital data can be relayed from sensors or from one "smart" device to another, based on the Internet of Things idea, and that data can then be collected and transmitted to other smart devices in real time rather than waiting for a human to see that data and act on it or send it somewhere else.

We want to emphasize that smart cities not only collect data, but they feed data back through all of the connected systems to allow changes to be made without the need for human intervention. Almost by definition, a smart city needs to share data across previously discrete and disconnected systems.

The topic is too broad for us to discuss in all of its aspects, so in this article we stick with the community development and city planning applications and implications of digital technology that we think will be useful to local jurisdictions. It goes without saying that we applaud every improvement in municipal efficiency and responsiveness, but we can offer the best insights into how transportation, land use decision making, worthwhile community engagement, and public safety can be improved with more connectedness and better data through digital technologies. We will leave improvements in internal city efficiency to others.

Energy Use Applications in the Smart City

Let's begin with smart energy conservation strategies. Before we delve into street lighting, we should note that the smart city concept may involve collection of and interaction with private sector data. Conceivably private sector lighting in commercial buildings could be partially controlled through feedback about the performance of the electrical grid, for instance. A few industrial processes might be slowed or halted when there is an uptick of energy usage in other sectors. We are talking about consenting commercial and industrial firms here of course.

Now let's move on to more typical smart city projects. So-called intelligent street lighting represents a big potential savings. These systems dim the lights, sometimes turning them off completely, when no vehicle or pedestrian movement is detected by sensors. Usually the lights are networked to permit more efficient and complete coverage where needed. Corporations that sell these services are claiming as much as a 50 percent reduction in energy cost. This should mean less changing of the bulbs too. Such systems also could provide data about traffic volumes of all types, and potentially even the types of vehicles passing by at particular times of day.

The side benefit for residential areas especially is that less street lighting can mean a better dark sky conductive to sleep, providing residents feel confident that the lights will activate when they detect the movement of bad guys or gals, of course.

Now let's broaden the discussion to what else can happen on a light pole. Management of traffic lights also is possible through data sensing occurring on the pole. This technology already has been used in bus rapid transit systems for a number of years, and cities already are widening its applicability to all traffic situations. Residents' convenience, reduced consumption of fossil fuels, and air quality all will be enhanced if drivers no longer have to stop for a red light unnecessarily. And in theory, if there are no vehicles or very few vehicles waiting at the light in one direction, the light could respond by allowing the long line of cars and trucks traveling in the other direction to proceed.

Although it doesn't happen on a pole, you have no doubt encountered an early type of "smart city" energy conservation in the form of sensors embedded in the broad white lines at traffic signals. We have all learned to pull forward a couple of feet if the red light stays on for too long.

We once had a page on this website about the so-called smart grid. While we removed that page when it began to seem old and tired, at the same time, it is of obvious benefit to communities when the electrical grid is extremely resilient to shocks because there is redundancy within the system and sensors are speaking to one another about supply and demand, instead of waiting for a human operator to make mechanical adjustments.

Other Smart Technology Deployed on Utility Poles

Security cameras, owned both by the private and public sectors, also are very common on electric poles. You may not have associated these cameras with a smart city, and often you would be right. To our minds unmonitored cameras, with footage that is never reviewed unless and until there is an incident, don't make for a smart city. However, we have seen a number of cities thinking about how to use a constant stream of digital images that would make these cameras a smart device useful for detecting patterns of street usage and traffic ordinance violation or compliance. Obviously there will be a few data errors when images are interpreted by machines instead of humans, but these should decrease in frequency with more experience.

Gunshot detection technology also is being deployed on utility poles in many cities. The results so far are mixed, in our opinion. Some police departments have found this data to be useful, and some neighborhoods believe that the very existence of this technology serves to deter crime. The disadvantage is that there have been plenty of reports of false positives, in which some other noise triggers the gunshot alarm at police headquarters or in cars.

Parking space monitoring from cameras mounted on utility poles also is another function under experimentation. This can help municipal officials visualize parking patterns more efficiently. Potential for nabbing those who don't pay properly also exists, using license plate photography. When vehicles are equipped with networked technology, drivers will think the main benefit of living in a smart city is having access to real-time information about parking availability and traffic situations. A shorter search for parking also can help reduce pollution and maybe even inspire more face-to-face shopping in local stores.

If city personnel can monitor parking spaces effectively and automatically, they also can detect traffic slow-downs and react by recalibrating traffic signals temporarily or permanently, sending personnel to investigate when video or sensors don't clearly indicate what type of problem is causing the delays. Cameras or sensors also can identify problems with temporary traffic barriers such as those placed by utility and construction companies.

Pollution sensors also are being placed on utility poles and incorporated into the smart city infrastructure, and of course this is quite helpful in identifying specific local problem areas at a finer geographic level than the widely spaced air pollution monitoring stations in use now. Miami has been toying with the idea of paying residents to mount these air pollution sensors somewhere on their property.

Quick and localized flood detection, currently being studied by Oxford, England residents, could help prevent property damage and even dangerous conditions for residents.

We expect ever more sophisticated applications of this technology. Meteorological data can be collected in the same manner, and seismic data collection may be warranted in some locations. It isn't beyond reach to think of public health officials being able to monitor viral loads in a block or neighborhood through the use of air sampling.

Maybe temperature sensors could measure the ambient temperature not only at the utility pole but also within 10 feet of a building structure, thereby measuring heat loss.

Waste stream analysis could be conducted on a scale that would boggle the human mind. Applications might include everything from making recycling more efficient to identifying where food waste is most prevalent. On a more mundane level, if sensors or cameras can detect and report an overflowing trash dumpster in the alley, we call that real human progress.

Pavement sensors or sophisticated cameras might detect, report, and schedule the repair of potholes in the spring.

Data on locations and movements of likely homeless individuals might help social service agencies assist them more wisely. Obviously, any applications that monitor human behavior raise thorny issues about individual freedom, agency, and privacy.

We should emphasize that the smart city concept not only means collection of data from "smart" sources, but also the filtering of that data back through the system to enable automatic reaction and recalibration of other systems within the city. Imagine the improvement if the interaction of traffic, parking, and pedestrian movement to one location can be detected and then facilitated by adjusting traffic signals temporarily, suspending parking meter enforcement temporarily, and extending pedestrian light durations as appropriate to help people be safe but also less frustrated as they enter and exit a concert, sporting event, or other large gathering.

Communication Implications of The Smart City Concept

At an elementary level, residents might be able to download an app connected to its city's interconnected systems to predict traffic delays or parking shortages, and learn about flooded streets, utility work or emergency response slow-downs, the micro-climate across town, and how many people are signed up to speak at the city council or planning commission meeting.

Inexpensive broadband is another huge potential aspect of the conversation about smart cities, since broadband everywhere is important for equity among income groups, resident empowerment, economic development, and neighborhood attractiveness.

Equalizing the playing field among those unable to afford internet connectivity, able to afford only pokey internet, and able to afford and bright enough to order screaming fast internet should be a priority for cities. Older residents may not realize the extent to which schools require internet usage, including upload of completed homework, but obviously all students deserve equal opportunity to learn and have their work recognized.

Since "work from anywhere" has become very popular, good wi-fi other than in coffee shops and at home has become essential, and cities with dead spots for broadband will not be as attractive for new businesses and expansion of existing business.

New cell phone towers really aren't being sited in urban areas now; the sharp upward trends in demand for voice and data are being met by small cell technology in which devices are mounted on utility poles or elsewhere every two or three blocks, maybe every 500 feet. Since cell phones use large quantities of data also, look for convergence of small cell and out-and-about wi-fi within the smart city.

Yes, the communication aspects of a smart city come loaded with privacy concerns. Some cities use smartphone GPS features already, and in fact, private businesses may be doing so. Sensor technology also means you could be receiving those nasty push notices on your phone to an even greater extent than you already are. This will need some controls in the future; in fact, Amsterdam already has instituted a requirement for registering sensors, whether they are deployed by private businesses, residents, or governmental agencies.

License plate identification technology exists and is in use for purposes such as automatically generated e-tickets for speeding or running a red light (so-called "smart ticketing"). This technology could result in some truly undesirable side effects. Think about electronic billboards that would change, as you approached in your car, to advertising that cool new gadget you were looking at this morning on your home internet.

Or maybe existing facial recognition technology is applied to "pushing" an audio ad to you as you approach on the sidewalk, or maybe it tracks you as you walk around a business district or bar district.

How Will Smart City Technology Benefit City Planning?

So far this article has listed some elements of a smart city that might apply to community development and city planning, but has not zeroed in on the interaction among those elements. This is only because we want to spare you from excessive article length.

The major point is this: smart cities could generate fast and economical predictions of the impact of certain actions and decisions. This ability to identify and evaluate alternatives is the very essence of city planning.

A second important take-away for citizen planners is the potential of a smart city approach for narrowing the so-called "digital divide," which limits the access of people without good broadband connections to the detailed information, large maps, and interactive video calls inherent in online presentation of planning information. Expanding both elementary access to planning data and real engagement of residents in planning decisions should be a goal of all planning commissioners, elected officials, and planning and community development staff members.

On a broad scale, cities are experimenting with adding a third dimension to their GIS data and other public and private data sets by building digital twins. We won't say more about that here, since we have written a page on that concept by itself, but we will note how much more bearable it is to experiment with a robust virtual model of the city than to endure the monetary cost and the human cost of an actual experiment that could take months or years.

This capability to predict the results of future changes is fundamental to good city planning, and we hope that a smart city will embrace this concept, while never failing to recognize the problems inherent in poor data, missing data, and invasion of privacy.

Comprehensive consideration of data and the elements of a city is a central tenet of good city planning. If this tenet is true, the interoperability of many different data sets from multiple sources should provide a level of comprehensiveness that early city planners could only dream of. Indeed, creating a unified data portal, sometimes open to the public, is often touted as one of the accomplishments of some smart cities. However, that very interoperability presents many new problems with how one authenticates the comparability of different data sets. If the potential for Big Data seems too dystopian to you, our advice is not to worry much, because resolving such issues will take a long, long time.

In the meantime, though, if decision makers in both public and private sectors gain some new insights by being able to cycle more rapidly through possible scenarios, we think that is of enormous benefit.

If you would like to explore this concept further, the site we suggest is digi.city.

Read More About Relevant Connected City or Town Topics

- Making and Keeping a Good Community Development ›

- City Planning › Smart City

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.