How Power Mapping for Neighborhoods Can Be Helpful

Reviewed: June 20, 2024

Power mapping is usually considered a tool of community organizing. The planners who write for this website have had several experiences with power mapping for neighborhoods. When we chatted about our personal examples, we found that this tool that is popular with community organizers has been only partly successful. On this page we tell you about what makes this process work best, as well as what doesn't seem to work.

Power mapping as it is usually practiced involves creating some type of chart showing the relative importance of each person perceived to be critical to reaching a policy goal, as well as who influences that person and how to reach them.

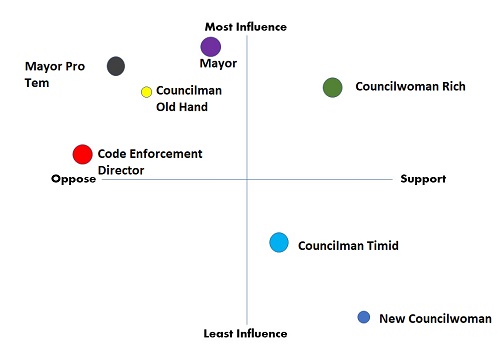

Organizers who use the language of power mapping speak of a “campaign” to achieve a goal and the “target” person or persons who must be convinced to allow or help the community achieve that goal. Often the community is encouraged to develop a chart that might look somewhat like the one below.

We hasten to add that neighborhood-level power mapping could take many forms and thus lead to many graphic representations, which we discuss below.

Advantages of Power Mapping for Neighborhoods

As you will see, our experience with power mapping has not been 100 percent positive. However, when neighborhood associations (or loose groups of neighborhood residents and stakeholders who come together for the purpose) use the tool in a smart way, there are some real advantages. We see three.

1. The identification of who the decision makers are in conjunction with a specific policy goal or the general welfare of the neighborhood is helpful both to the leadership and to the neighborhood association members. Getting past a vague “they” or “the city” who are seen to be oppressing the community or blocking a particular action makes achieving the goal seem more doable, and in addition, it allows the community to identify specific traits or quirks of the people who hold the power.

2. When neighborhoods do power mapping, residents are encouraged to think about how to move a seemingly immoveable object. Opening up thinking about possibilities instead of grumbling about problems and even internalizing the attitudes of the oppressors builds hope and agency among the people. This in turn increases participation, which then leads to true engagement.

3. The exercise should lead to increased effectiveness in even contacting and interacting with a very busy person. In every city of maybe 50,000 population or more, there is at least one gatekeeper to a person who holds a considerable amount of power. The mayor will have a lieutenant (who may or may not be on the payroll), and council members also have a staff person or someone they listen to, who fields requests that for that decision maker’s attention. In many instances, knowing the gatekeeper is critical to having access. In neighborhood power mapping, you should discover who that person is.

Why Are We Somewhat Skeptical About Neighborhood Organizations

Using Power Mapping?

For all of the above reasons and more, we applaud the use of this technique for major community organizing campaigns aimed at citywide goals. Below we are going to tell you why we would like to see neighborhood organizations that use this tool soften some of the language surrounding power mapping.

Quite simply, we don’t like the convention of describing people as “targets” any more. It made perfect sense once upon a time in the history of community organizing, but today there is too much violence for us to be comfortable talking this way. I saw an instance of a young person in a meeting who thought for a minute that others were discussing violence against a person.

Now it strikes us that the target language also dehumanizes the person to whom it is applied. We prefer to call that person a decision maker, or maybe a key influencer or key participant. This sharper language helps community members identify the true role of the person that they perceive to be standing in the way of what the neighborhood wants.

We also have become skeptical of the power language itself. All of us who have participated in neighborhood or community-wide level actions and campaigns recognize that power is real and important, and that people of color, women, disabled people, children and youth, and certain ethnic groups often do not have much power at all.

However, when neighborhood leaders constantly talk about the people who have the power to change this dynamic that we are worried about, it implies to the residents that they do not have the power. But the fact is that in a democracy, ordinary people have a lot of power. To unleash that power, they simply have to learn how to harness it, how to be strategic in how they spend their energy, and how to express their goals in a compelling way.

This brings us to a final point about the power mapping approach. We think that you have to know what you are talking about. Achieving your policy goals and concrete actions usually does not occur simply because you applied an unbearable amount of pressure to some people.

There is an element of logic, rationality, and evidence-based proposals in most satisfying campaigns that achieve success in the long term. If you merely convince the power brokers that they have to “do something about” a topic of interest to you, their actions may or may not contribute to solving your problem. So do your research about the root problem and the best likely solutions. If you need help with this, see the sitemap of this website as a good starting place.

How to Do the Power Mapping at the Neighborhood Level

Our chart above is just the starting point for your work. The real value of power mapping is to explore the connections and associations between each person you have chosen as a potential decision maker and other people in their lives. If you can make your diagram large enough, you can map these associations on the same large piece of paper, or more likely, a series of large pieces of paper that you have taped together along a wall.

Here's how to begin to look for each person's connections. Write down the names (if known, and if you don't know names, just jot down a description of the category) of your decision maker's family members, election campaign contributors, staff members, bosses, work colleagues, business associates, fellow congregation members you know, fellow civic organization members (such as Rotary Club), fellow PTO members, fellow golf or tennis club members, immediate neighbors, media personalities you have observed that person being friendly with, household employees such as nannies or house cleaners, and any personal friends from other associations that you are able to uncover.

We can't bring ourselves to suggest using social media accounts in devious ways, but to the extent that you and others involved in neighborhood power mapping come across social media from the decision makers, note who makes encouraging and supportive comments. We cannot bring ourselves to suggest less than honest social media usage, but we know some of you will be pretty crafty about figuring out who speaks for whom.

Of course, we do recommend using search engines to see what you can learn.

Put the decision maker names in a circle or other shape of your choice, possibly making the shape significant. Link decision makers with their influencers by drawing lines between the associate and the primary decision maker. Lines and shapes can be color coded. You also could use the style or color of lines to indicate how sure you are of this association, whether anyone in your group knows that associate, and so forth.

Those are the basics of creating your power map diagram. You will find that the chart looks different for each project. There is no one correct way to do this; you will have to be firm with group members who have had maybe one experience with power mapping but are certain that their way is the only correct method.

Further, we can assure you that our experience has been that the power map will be corrected and changed as you go along, especially if it takes months or years to achieve your objective. So don't let perfection be the enemy of just getting started based on really obvious and publicly available information, such as spouse and kids, employer, election campaign contributors, and next door neighbors.

But we do have some tips about the process for creating your image and any work sheets you want to associate with it.

First, we recommend involving as many residents or other stakeholders (such as large institutions or businesses who are active in your community) as possible. Don’t let the community organizer or the project leader or the president or board of the neighborhood association do all the work.

Why do we say this? Some will object that the leadership or outside organizer who is helping will have superior knowledge of how policies and conditions are changed in your city or area. While that is certainly true, our experience has been that when we broaden out the number and types of people who are engaged in the project, you are building the depth and the capacity that will be needed in future projects and campaigns. The more people who understand the power structure and how to influence it, the better.

So while you might need a steering committee or a specific officer or small group to be in charge of planning your events and research, be sure to keep all of the people who are standing around on the periphery aware of how you came to the knowledge that you have, and how to research ways it may change in the future.

Second, be careful and comprehensive in identifying who must change their mind or become more passionate for you to achieve your goals. Sometimes the off the cuff reactions when you pose this question to your membership will be just plain wrong. Make sure that you have someone or several people who understand the formal and informal structure of the public body or official that must make a decision in your favor.

Again, don't go through this step so quickly that the people who are less familiar with the power structure are left just to nod their heads or be silent while someone records what the leaders think. If you do the latter, you will complete your power map and have a nice chart, but you won’t have developed any new potential leadership.

Third, where it is feasible, assign some people who are newer to the group or to being active in the organization to research who influences the decision maker(s). By this we mean that sometimes it is easy enough to find out that the mayor has a chief of staff, a chief of policy, and a secretary who is the niece of the most important businessperson or council member. In most places you can learn who contributed to political campaigns and figure out online who those people are.

We recognize that in some instances, the people who pull the strings are really hidden behind the curtain. Newcomers to your organization won’t know this and won’t have a clue as to how to find out. Thus we are not saying at all that you could leave all of the influencer research to people who haven’t been involved before. But to the extent that some patterns of association, connection, and influence are fairly obvious to someone who does a little digging, and neighborhood leaders should encourage spreading out the work.

Fourth, because we like adding depth to your campaign through broadening the circle of folks who understand and contribute to the power mapping, it unfortunately means slowing down the process. We suggest that you shorten the timeline as much as possible, consistent with letting new people into your process. If you meet every week for a month, you will have a more than adequate power map. In a neighborhood where people are educated (formally or informally) and motivated, it may be that two meetings with a two-week interval in between will accomplish the work.

This does not mean that all action must stop while you complete the power mapping. Some decision makers are completely obvious, and you can begin immediately to figure out how to reach them and how to change their minds.

Read More on Relevant Topics

- Community Development ›

- Community Organizations ›

- Appropriateness of Power Mapping for Neighborhoods

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.