Community Mental Health Approaches Could Reduce Homelessness, Some Types of Crime

Last Updated: May 22, 2024

Community mental health often is defined as the movement to provide services to the mentally ill out in the community, rather in a large institution in a remote location. We have a broader concept in mind.

For a few decades the best of our social science has been telling us that chronic stress may be a strong contributing factor to mental illness in some individuals. Sure, strong genetic, family dynamic, or traumatic event factors may predominate in certain individuals. But we consider mental health to be a community issue because cities and neighborhoods can decrease the following elements of chronic stress to some extent:

- Poverty

- Discrimination

- Exposure to violence and domestic violence

- Lack of safe and affordable housing

- Incidence of hate crimes

- Culture tolerant of bullying

- Food insecurity

- Poor job prospects

Friends, until your community gets serious about these major issues, which are at least partially under your control, you will continue to experience the unsettling and chaotic impacts of chronic mental illness in your neighborhood, town, or city.

We believe that the work your cities, neighborhood associations, and community development organizations already do can contribute toward the reduction of addiction, violence, depression, homelessness, mental health-related poverty, extreme reactions to disagreements and perceived slights, and family dysfunction and distress.

This page is organized into three categories of community level action promoting mental health:

- Prevention

- Crisis intervention and treatment

- Support and services in non-crisis situations or the post-crisis time period

Community Factors in Preventing Mental Illness

I begin by asking why explicit prevention programs are not more prevalent. Largely we who write for this website see this as a matter of political will. In our conversations with them, short-sighted legislators often look simply at the up-front cost of providing high quality prevention, treatment, and aftercare, without thinking about the long-term social and financial costs of crime, substance abuse, homelessness, and family turmoil that may result from mental illness--or be a factor in its causation.

But why is there a lack of political will? One answer is that our concept of individual freedom has become so strong that many people object vigorously when there is any attempt to intervene, even in the face of severe threatening behavior or obsessions.

Legislatures have enacted increasingly aggressive laws protecting the rights of the mentally ill or someone accused of being mentally ill from being treated against their will.

In most situations people can't be detained against their will for more than 72 hours in most states. That's just long enough to prescribe some medication, hope the patient takes it, and suggest vaguely some follow-up. This simply isn't adequate in a society where:

- The drugs themselves cause a variety of quite undesirable side effects that aren't necessarily recognized and treated seriously enough by mental health professionals.

- Housing becomes problematic when one is institutionalized for a month, unable to work or pay the rent, and then as a result, unable to rent other suitable quarters.

- Guns are freely available.

- Solving problems through violence is increasingly popularized and glamorized on our entertainment media and by some entertainers and sports figures.

As a person who had to deal with mental illness of a family member within the past 20 years, I can tell you definitively that until the person decides to get serious and prolonged help, the resources for community confrontation and detention are meager. The legal and confidentiality protections are all on the side of the person who needs help, and not on the side of family members or community members who are at risk because of the person's erratic behavior.

A second reason behind the lack of political will is even more important. In the U.S. at least, our decision makers are reluctant to tackle big topics at the national and state levels. Going back to our original list of chronic stressors that intensify mental health risks, we see most of our elected officials as unwilling to do the hard work of researching potential solutions to poverty, discrimination, violence, and housing, food, and job insecurity.

If you're a neighborhood or community leader who also would prefer to stick your head in the sand in the face of these overwhelming and massive issues, of course you may. But while you're looking for a graceful exit, let me challenge you to think of the percentage of your community's budget that is spent on police work, and then to look at what happens to law enforcement spending when a community reacts to a major crime.

And if money doesn't move you, human misery may. The exposure of children to street violence, domestic violence, addiction, and homelessness often scars them in ways that pass misery to future generations.

In the final analysis, local and community leaders have the most to gain from effective programs for mental illness prevention, which happen to be the very same programs and projects that neighborhoods, towns, and cities already initiate.

Do you see why we think community mental health is an integral part of community development? Relieving chronic stressors is the same work that solid community development programs and organizations already do. There are no simple and comprehensive solutions to these chronic stressors, but persistent local leaders who don't have to heed election cycles are more likely to make a dent in these problems than the state and national leaders who are pulled in many directions, are too polarized from one another, and often face elections or term limits. The state and national leaders have the advantage of a skilled staff, but you local leaders have the advantages of granular local knowledge and emotional investment in outcomes.

Progress in this area really is possible. If you doubt this, please look over the youth-oriented Text, Talk, Act initiative, which features both text-facilitated community dialogue approaches to mental health and practical tips for talking with a friend in need. Because a cell phone and 4-5 people are the only tools needed for a successful conversation, this may be accessible and appealing for the intended young adult audience.

A second example of effective community prevention is the mini-movement toward a restorative justice approach for comparatively minor offenders. In this intense approach, local officials and community members bring offenders with less severe behavioral issues into a room with victims and community representatives to help them understand the true impact of minor crimes they commit. Sometimes this is part of a court watch program, which is definitely worth a look for those who are interested in community approaches to mental health issues. We've provided a little introduction to court monitoring for neighborhoods here on this website.

The Classic Community Mental Health Treatment Approach: Short History

It has now been more than 55 years since Congress passed the 1963 community mental health law, which led to widespread "de-institutionalization" from state "mental hospitals." we have removed the stigma from mental illness to some extent. However, we continue to suffer from inadequate implementation of the community mental health movement.

The problem is that when large mental hospitals dismissed patients in the 1960s, there wasn't enough attention to exactly how the community would deal with mental illness.

Upon passage of that community mental health act under President Kennedy's leadership in 1963, the reality was that some states viewed community clinics as a relief from the financial obligation of running large state hospitals.

They released hundreds of thousands of patients with no little to no planning for how ongoing needs would be addressed. The law's promise of incorporating every part of the nation into a "catchment area," or service area, never came to pass. The goal was to create 1,500 community mental health centers, but fewer than half ever were built. A reinvigorated law passed at the end of the Carter Administration was nullified by the Reagan Administration, which favored block grants to the states instead. As you can guess, some states did a great job, but one of the authors of this website worked in a state where nothing much happened.

Many of the organizations created in the sixties survive as CBHOs (community behavioral healthcare organizations). They do great work, and the general thrust of the law, that we shouldn't permanently warehouse mentally ill people in large hospitals, certainly holds true.

However, we still have geographic areas not covered by these community clinics, many of which are overworked and understaffed, and most do not offer enough of the substantial aftercare needed after persons have been in treatment for a mental health or substance abuse issue.

What Communities Need to Know About Treatment Today

In working with communities, I have found three major barriers to effective mental health treatment. The sharpest of our community development consulting clients have tried to move the dial on each of these.

First, despite our best efforts, mental health treatment still is stigmatized in many quarters.

This is particularly true in some congregations and among the military. Many businesses are inept about handling mental health in a sensitive and reasonable manner too.

Schools often identify young people in trouble, but either their institutional framework makes an effective intervention impossible or unlikely, or sometimes parents object vigorously, all due to stigma we imagine.

Second, mental health treatment may lack sensitivity to or simply knowledge about cultural differences and religious beliefs.

Therefore it is more effective with some populations than others. Think how urgent community mental health needs may be among refugee groups, but without an appreciation of trauma and other cultures, an incorrect course of treatment would be very likely.

Third, people receive mental health treatment if they can afford it, and they either present themselves for treatment because of discomfort, or have a severe episode and agree they need to be treated.

Ideally, from the perspective of the current money-driven health care system, the person can be placed on medication and seen infrequently, rather than placed in a more expensive talk therapy program.

Since finance seems to be the determining factor, the society seems to think we can't afford a multi-pronged approach including talk therapy, medication as needed, peer counseling, and family, employer, and community involvement. I think that's a big mistake for communities and a loss of human productivity for society.

Communities have to become really creative to compensate for this problem, which is created and sustained by the broader society. To overcome the lack of healthcare system resources, local communities have to break down customary silos by bringing together leaders from schools, local government, police departments, mental and physical health systems, business, and neighborhoods. Building and sustaining a coalition, similar to those used in the community anti-drug coalitions, seems most likely to be successful. The next section presents a specific model.

Hopeful "Best Practices" in Community and Public Mental Health Treatment

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is the most promising notion I've seen yet for doing what community and neighborhood leaders all know needs to be done. In the U.S. it's promoted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in the Department of Health and Human Services.

This approach is designed to provide the intensive support that many individuals need to successfully move back into the community after a traditional program of mental health therapy.

In this team-based concept, caseloads (the number of persons a staff member is working with) are kept low, so that the ratio of workers to individuals being served is no lower than 1 to 10. The team includes employment specialists as well as various mental health disciplines.

For example, the state of Washington operates a Program of Assertive Community Treatment that exemplifies the vision. They claim that 75%-85% of outreach occurs within the community. In community outreach, interdisciplinary teams look for individuals who have more than one disorder (perhaps a mental illness and a substance abuse issue) on a severe, recurring basis.

Neighborhoods and communities, isn't this kind of community mental health what we need? Doesn't someone with appropriate training need to go out and look for individuals who are "de-institutionalized" but still not adapting successfully to community life?

For more information on Assertive Community Treatment, find the U.S. government's free downloadable ACT kit booklet about an evidence-based practices approach. Written for the mental health practitioner audience, but understandable to all, the booklet describes how in Alameda County, California, found the program less costly than a more traditional approach to service delivery.

Let's figure out how we're going to proactively plan locally to prevent and treat mental illness, and support continuous mental wellness through working on the chronic stressors that community development can impact: poverty, violence, discrimination, homelessness, and food and job insecurity.

Let's build the social capital that can provide ongoing emotional support without the need for elaborate institutions and programs.

Supporting Ongoing Mental Wellness

Our experience has been that there are three main reasons that ongoing support for mental health is not available: (1) lack of funding for outpatient community mental health facilities and services, (2) lack of appreciation for the fact that mental health is not a condition with an "on" switch and an "off" switch, and (3) poor implementation of the concept of "mental health parity."

This latter factor requires a little explanation. Mental health parity means that mental illness and physical illness receive equal health insurance benefits. This concept has been recognized in law and reinforced in the Affordable Care Act, but the co-payments required by my particular health care plan still are considerably higher if I want to treat depression than if I stub my toe. In my plan now, I have to call and describe my problem before the plan will refer me to a practitioner, whereas if I have the flu, I can check out the list of physicians and call the one I want without having to go through humiliation to get there.

We bet your health insurance is similar.

Compounding the problem even further, there is very little attention in society as a whole to the need for supportive services during the re-entry period following hospitalization or a severe episode. Those service needs might extend beyond treatment to items such as housing in a more suitable environment or education to allow entry into a successful career or a change of careers.

Summary

Here's why community leaders need to devote attention and community organizing to this issue. It's in the sweet spot of community development anyway, at least to the extent that you share my belief that community development is more than real estate development.

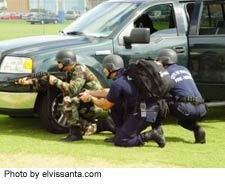

While I wholeheartedly agree with those who believe that reform of gun laws is essential in the U.S. if we wish to deter mass shootings, there is plenty of room for working on community identification of mental health needs, effective methods of getting help to those who need it, and practical techniques for deploying mental health officers along with police officers.

If you do what you usually do to relieve the chronic stressors that often make mental illness possible, but just do it better, then decreases in crime, domestic violence, homelessness, and traumatic experiences for kids could be your positive result. When combined with other physical, social, and economic improvements, neighborhood stability and reinvestment surely will follow.

Read More Pages Related to This Topic

- Making and Keeping a Good Community ›

- Community Challenges, Common Topics & Concepts ›

- Crime Prevention > Community Mental Health

Join GOOD COMMUNITY PLUS, which provides you monthly with short features or tips about timely topics for neighborhoods, towns and cities, community organizations, and rural or small town environments. Unsubscribe any time. Give it a try.